Japanese animation legend Hayao Miyazaki’s new film is said to be his last – and, with its reflections on life and death, it certainly feels like a farewell. But is it really the end for him, asks Stephen Kelly.

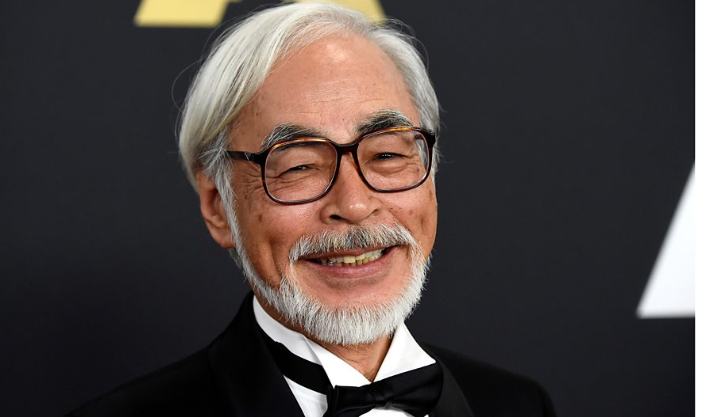

The Japanese animation director Hayao Miyazaki, a workaholic auteur generally considered to be one of the artform’s most accomplished masters, has been trying to retire since 1997.

Back then, it was the thematically rich Princess Mononoke, a record-breaking Japanese box-office smash, that was to be his final film. Then, in 2001, it was to be Spirited Away, the sumptuous mega-hit that announced Studio Ghibli, the production company co-founded by Miyazaki and the director Isao Takahata (who died in 2018), to the world. And in 2013, he said the same the thing about The Wind Rises, a loosely autobiographical film about the development of the Mitsubishi Zero, Japan’s most famous warplane.

“I know I’ve mentioned I’m retiring many times in the past,” he told a press conference that year, “so I know that many of you might think, ‘oh again’. This time is for real.” Cut to 2023: the long-anticipated release of Hayao Miyazaki’s final final film, The Boy and the Heron. Or is it?

With Miyazaki now 82 years old, his eyesight fading, his hands not as resilient as they used to be, you could be forgiven for believing him. Speak to his colleagues at Studio Ghibli, however, and they describe a director as determined and demanding as ever; a man for whom idleness is anathema, who will never, ever stop.

“At first, I could sense that he wanted this to be his final project,” veteran animator Takeshi Honda, who worked as The Boy and the Heron’s animation director, tells BBC Culture. “But I could sense time and again that he’s not finished, that there are other things that he wants to do.” Speaking through a translator, Honda cites Miyazaki’s penchant for suggesting stories to adapt. “Sometimes he would just come to me and say, ‘listen, this novel is really interesting, you should read it!’ and I was like ‘what is this all about? What is he trying to make me do?’ Moments like that made me doubt his intention to retire.”

Studio Ghibli vice president Junichi Nishioka is even more forthright. “Even now there are new ideas that he talks about,” he tells BBC Culture, referring to reports that Miyazaki has already started work on a new film. “He is not physically working on sketches based on these as of yet, but I don’t think he will ever be ready to retire. I don’t think he’s ever going to really let go. He will have a pencil in his hand until the very day that he dies.”

Even if, once again, it transpires to be true – that The Boy and the Heron is not Hayao Miyazaki’s farewell after all – that does not stop it from feeling like one.

A deeply personal story

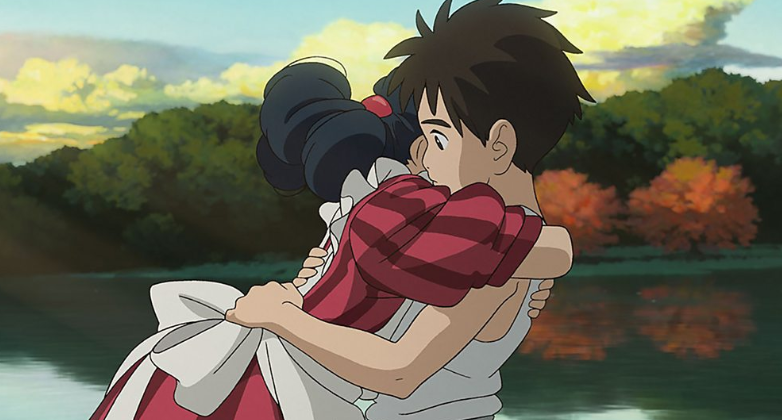

The film has opened in the US this weekend, but when it was released in Japan earlier this year, it arrived amid the unorthodox decision – taken by Studio Ghibli president Toshio Suzuki – to forego a conventional marketing campaign. No images. No trailers. Not even a synopsis. Instead, as they sat in their cinema seats, the lights fading low, Japanese audiences found themselves with no idea of what they were about to watch: the hauntingly elegiac, often breathtakingly beautiful tale of Mahito, a 12-year-old boy struggling to come to terms with the death of his mother.

It is, says Nishioka, a personal story for Miyazaki. “The Wind Rises was inspired by his early days as an animator,” he explains. “But with The Boy and the Heron, Miyazaki wanted to go back even further to his childhood.” Indeed, the film’s opening scene – in which Mahito runs through the aftermath of a US air raid on Tokyo – is inspired by Miyazaki’s experience of growing up during World War Two. It is an astonishing feat of animation: an expressionistic blaze of frenzy and flame, fear and panic, like a nightmare come to life.

“It has so many elements in there: the fire, the smoke, the people in the background,” says Honda, who took charge on animating the sequence. “We wanted it to have a celluloid look, a sakuga finish,” he says, referring to the anime term for a scene that is notably higher quality than others. “It was very labour-intensive, time-consuming and cost-consuming!”

Much like an infant Miyazaki, Mahito is evacuated from Tokyo to live in the relative safety of the countryside. It is here, tormented by grief, living miserably with his father and his father’s new wife, that he meets the titular Heron: a bewitchingly grotesque half-man, half-bird creature – voiced by a guttural Robert Pattinson in the English-language version – who tauntingly tells Mahito that his mother is still alive. It is around this point, as the fish chant for Mahito to “join us”, as the frogs clamber over his face, that The Boy and the Heron takes a turn for the strange. Having followed the Heron, Mahito finds himself stranded somewhere between life and death: a harsh, melancholic world, populated by the starving spirits of the dead and the embryonic souls of those not-yet-born.

Miyazaki wanted to make a picture that was more serious and sombre,” says Honda, who decided to reunite with the director after working on The Wind Rises. “He challenges you,” he says, “he expects something on another level. I knew it would be a test. I had already braced myself, having known other Ghibli movies. I knew what I was getting myself into!”

The production lasted seven years, with a team of 60 animators working at around a pace of one painstakingly hand-drawn minute a month, at a cost that has made it one of the most expensive Japanese films ever made. This is, in part, due to the audacious decision not to seek external financing, meaning that Miyazaki was not subject to a deadline.”So in effect you’re seeing an independent film here,” says Nishioka. “We didn’t have to lock the picture at a certain date, because we didn’t have any release commitments. It was very much Suzuki’s idea. He wanted to see what kind of picture Miyazaki could make without time constraints.”

How do we live?

Before he died in 1994, the terminally ill British writer Dennis Potter spoke of how the imminence of the end allowed him to see the world anew. No longer was a blossom merely a blossom, he said, “last week looking at it through the window… I see it is the whitest, frothiest, blossomest blossom that there ever could be.” These kind of transcendent observations have, in essence, always been the beauty of Miyazaki’s work: the steam rising from a bowl, a raindrop falling on a pebble, the wind rustling through grass. A pencil as a tool to sharpen the world. The Boy and the Heron is no different. It is dark in sensibility, gothic in atmosphere, but with Miyazaki being afforded a wealth of time and freedom, it also finds him at the peak of his powers: his images painterly and sublime, his narrative sophisticated and complex.

Miyazaki’s stories tend to eschew the more conventional plotting of western animation. They are studied, understated, often open to interpretation. A result, perhaps, of his penchant for storyboarding without a script. Yet more so than any of his previous films, The Boy and the Heron feels like the director’s subconscious run amok. The realm he has made is governed by ancient and unknowable laws, its array of imaginative ideas charged with symbolism and mystique. Where is this world? What is the birthing room? Who are the cannibalistic parakeets? It is a film compelling in its ambiguity, striving to be felt rather than understood.

“There was a lot, honestly speaking, that I did not understand,” laughs Honda. “I’d be like ‘what are you talking about?’ But Miyazaki would just say, ‘it is what it is’.” He admits that the film only began to make sense to him when he saw it in its entirety. “I think with this film, he is trying to tell the younger generation: ‘OK, here’s what I think’, but it’s not an explanation. He is trying to say, ‘when you all look at animation, you’re always so desperate for an answer. But maybe it’s time you think for yourselves.”

One aspect of The Boy and the Heron that seems unambiguous is Miyazaki’s reckoning with the big questions of life and death. In Japan, the film was released under the title How Do You Live?, a reference to the well-known 1937 children’s book written by Genzaburo Yoshino, read by Mahito. It is a question that has haunted Miyazaki, a director perpetually torn between optimism and despair, for most of his career: how do you live – as one character in The Boy and the Heron describes it – in “a foolish world rampant with murder and thievery”?

This time, however, it is a theme interwoven with Miyazaki’s own reflections on legacy. At one point during the film, an old man poignantly pleads with Mahito to take over this fantastical world he has created – represented here by a small tower of precariously balanced blocks – lest all of its wonder vanish forever. It is a scene that suggests a man coming to terms with his own mortality, with the idea that once he passes, there will be no one left who can balance the great blocks of Studio Ghibli. Or perhaps, without getting into specifics, the film’s ending suggests another interpretation: legacies, successors, even art itself, none of it actually matters. All that matters is that people – Miyazaki’s family, his friends, even the audience – continue to live on, to engage with the real world rather than retreat into fantasy.

“I don’t think he thinks of himself as carrying this torch of Japanese animation,” says Nishioka. “Nor does he dwell on his successor. But there are certainly times when he does think, ‘what is going to happen with Studio Ghibli after I’m gone?'”. The answer, adds Nishioka, will not be up to the old guard of Studio Ghibli, but to the younger generation, including Miyazaki’s 56-year-old son Goro. In a move reminiscent of Mahito himself, Goro, also an animation director, has declined to succeed his father at Studio Ghibli. Instead, Nishioka says, he will look after it in partnership with Japanese broadcaster Nippon TV, which recently acquired a majority stake in the studio. “Whatever they plan to do going forward, I don’t think it’s business for us to meddle in, but we have sown the seeds to give them choices,” he adds.

“[The future direction of the company] could be with the Ghibli Park [the theme park that opened in Japan last year]. It could be with new films that they will be producing and making.”

Acknowledging Miyazaki’s advancing age, Nishioka compares Studio Ghibli’s future with the state of US animation giant Disney during the 60s and 70s. “After Walt Disney passed away,” he says, “their business was quite low for about 10 years. But then they had producers, they had this new theme park. They were able to carve new pathways for themselves to not have to rely on just their classics. And I think, although I’m talking on a completely different scale here, Ghibli probably would do something like that.”

But of course, it is far too early, far too unlikely, to think about the unthinkable. After all, Hayao Miyazaki has another final film to make.

The Boy and The Heron is out now in the US and is released in the UK on 26 December.